Published on: 15,Jul 2024

Candace Imison, Deputy Director of Dissemination and Knowledge Mobilisation, National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR).

Two pressing and interconnected public health challenges are the rising number of people living with multiple conditions, and inequalities in health. A recent projection (March 2024) published in the Lancet suggests that if current patterns continue, the proportion of the working-age population living with multiple chronic conditions will keep growing, and socioeconomic inequalities will deepen. The authors argue that “the growing burden of multimorbidity will have profound impacts on the day-to-day lives of the population, increase demands on health-care and social-care systems, and lead to substantial productivity losses from sickness days and non-participation in the workforce and society.”

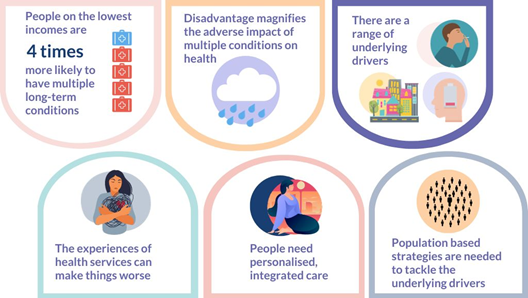

The National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) has invested significant resources in researching multiple long term conditions, the underlying causes, the impact on individuals and their health as well as their prevention. In 2023 we drew together the evidence on multiple long term conditions and inequalities in a Collection for NIHR Evidence. We looked at how discrimination and disadvantage increase the likelihood of multiple conditions, what drives the variation between different groups of people, the implications for health, and how services can help. The evidence is stark. Disadvantage significantly increases your likelihood of having multiple long term conditions, have poorer health outcomes and may experience services that exacerbate rather than improve your conditions.

Unfortunately, clear evidence about underlying causal mechanisms is scarce. Mechanisms are frequently hypothesised, but rarely tested. These include health related behaviours, access to material resources, and psychological response to social inequality.

Ethnographic research by the Richmond Group found factors at play included the type of work people did, including their working patterns and hours. The area they lived in, the quality of their environment and access to services all had an impact. Their financial circumstances had implications for their lifestyle. The other people they interacted with, and their underlying beliefs about the world around them, played a role. Many had developed unhealthy habits, such as a poor diet and lack of exercise, which were hard to break.

“I would leave home for work at 5am and come back after 11pm, then do the house chores. So I’d just drink coke and eat cake throughout the day. It was quick to eat and gave me energy.” – Vera – a retired cleaner

The current health system does not help. It is structured to manage single rather than multiple conditions. The needs of those experiencing the greatest health inequalities are too often neglected or even made worse by services’ response. This includes people from disadvantaged backgrounds, minority ethnic groups, and those with serious mental illness. The evidence demonstrates the importance of services tailored to the needs of their local communities, in particular the most disadvantaged groups. More bespoke support could help people adopt healthy lifestyles, understand and manage multiple conditions, and reduce their prescribed medications. Population-based strategies are needed alongside service-level changes, to tackle the environmental, social and economic determinants of health.

Tagged with: